Jo Boaler is the Nomellini & Olivier Professor of Education at Stanford University. She teachers Curriculum and Instruction in Mathematics at the GSE, which trains new teachers on math instruction.

Key points

- Provide varied opportunities for processing via drawing, reflecting, and reading

- Build class culture by getting student input and then codifying norms

- Be intentional about taking class time to think, talk, and share about experiences

How do you approach using interactivity in an online environment?

Well, I think one of my first principles in teaching online is: we want students to be as active as possible. In my own teaching, I am using video, Zoom calls, and building in other apps and tools to encourage interactivity. It would be sad if people thought that teaching online meant losing interactivity and just having teachers talking, and students listening; that would mean a lot of checked out students.

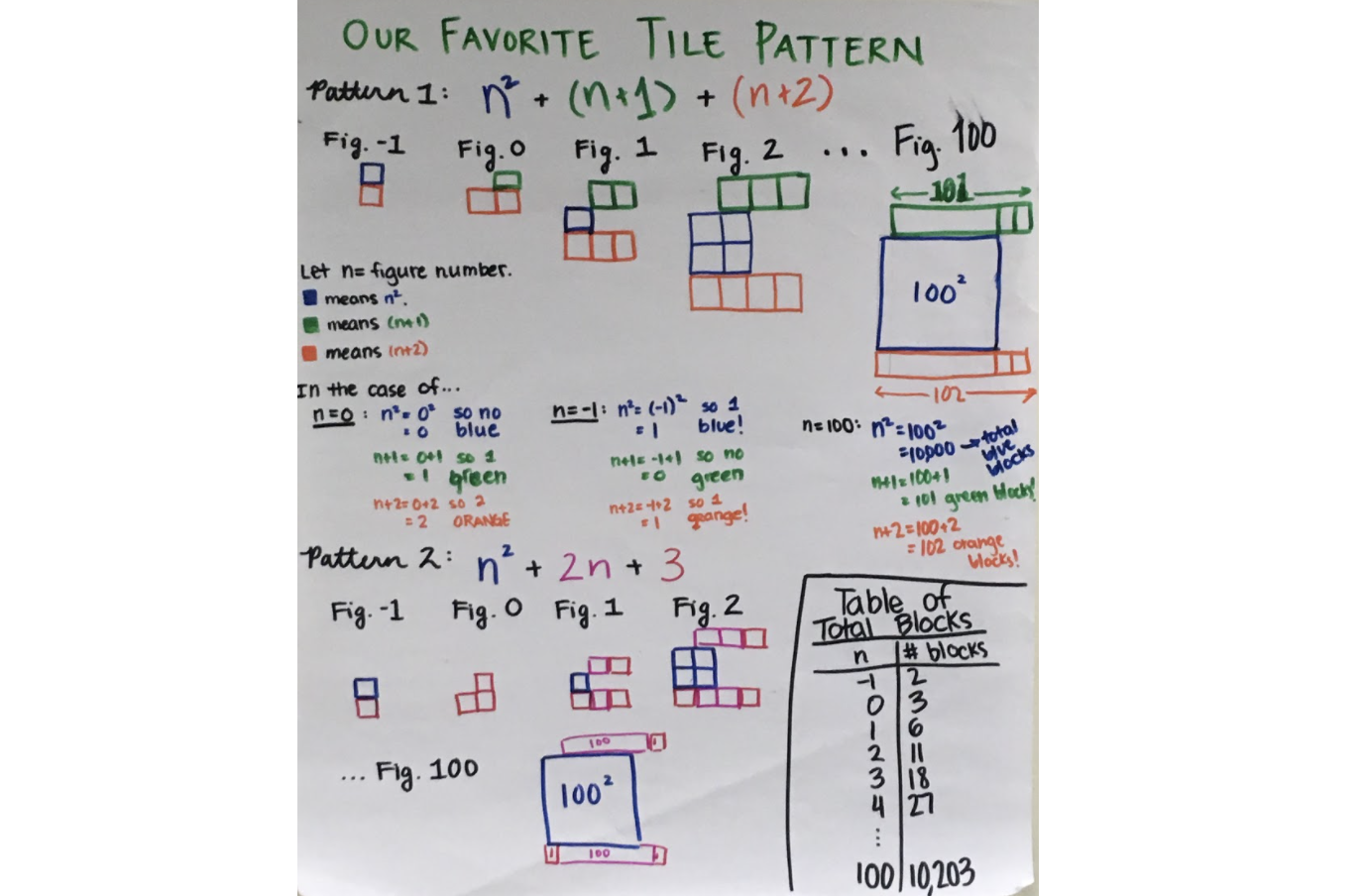

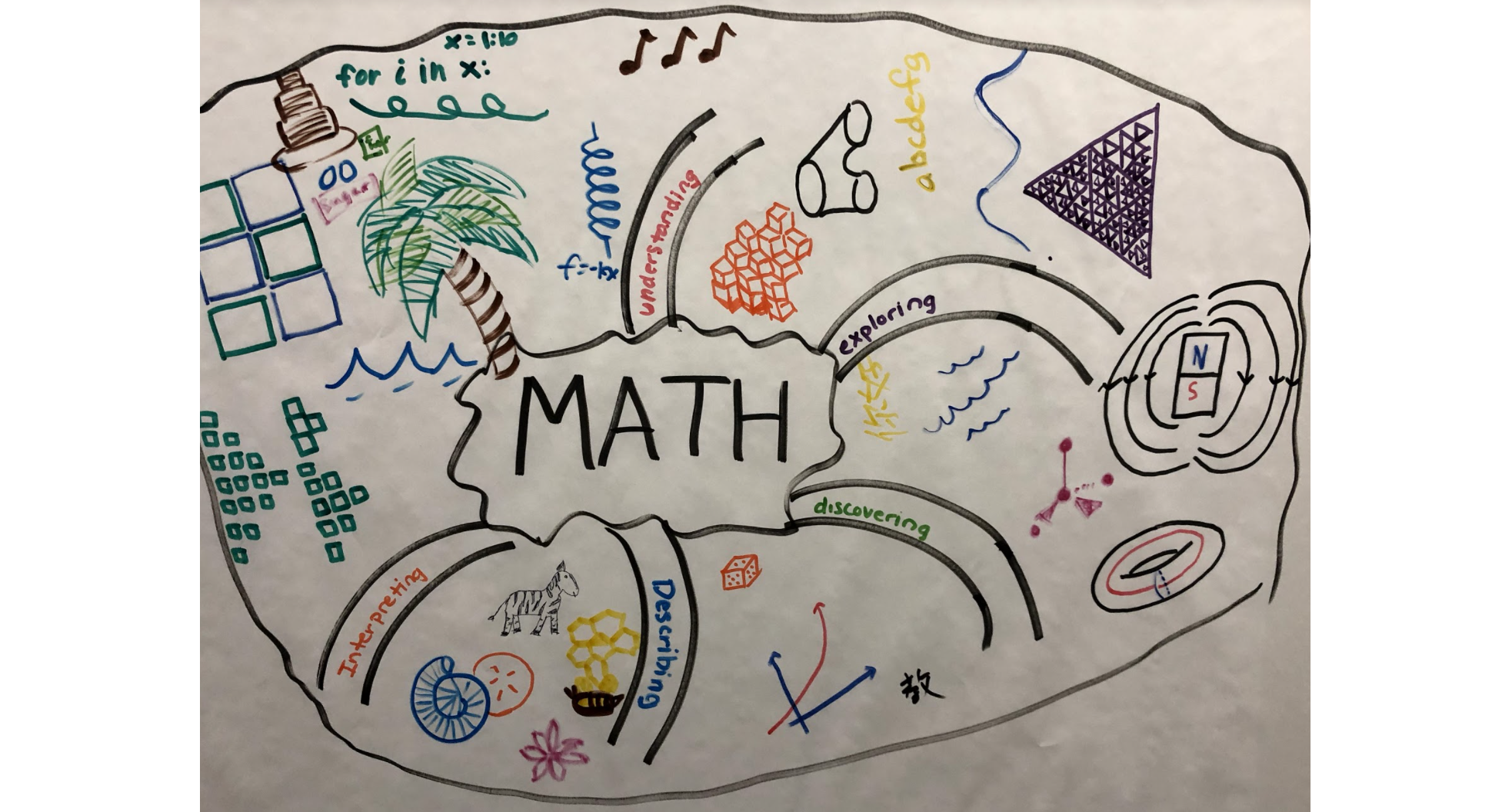

In my classes I want students to be excited by and working on really interesting maths. So I use a tool like Zoom to start a class together then break into smaller groups where people are working together. And I would have students working on something exciting with big whiteboard spaces for them to think creatively.

In my classes I want students to be excited by and working on really interesting maths.

We usually give our students journals. In fact, in my own teaching in a new teacher class at Stanford, I’m going to get my student’s journals so that they can be drawing. To work together on things, I’m going to invite them to a shared Jamboard space, which is a free online whiteboard. Inside Jamboard, students can be drawing and working on problems and collaborating together.

How do you encourage collaborative reasoning within an offline space? How does this translate to an online space?

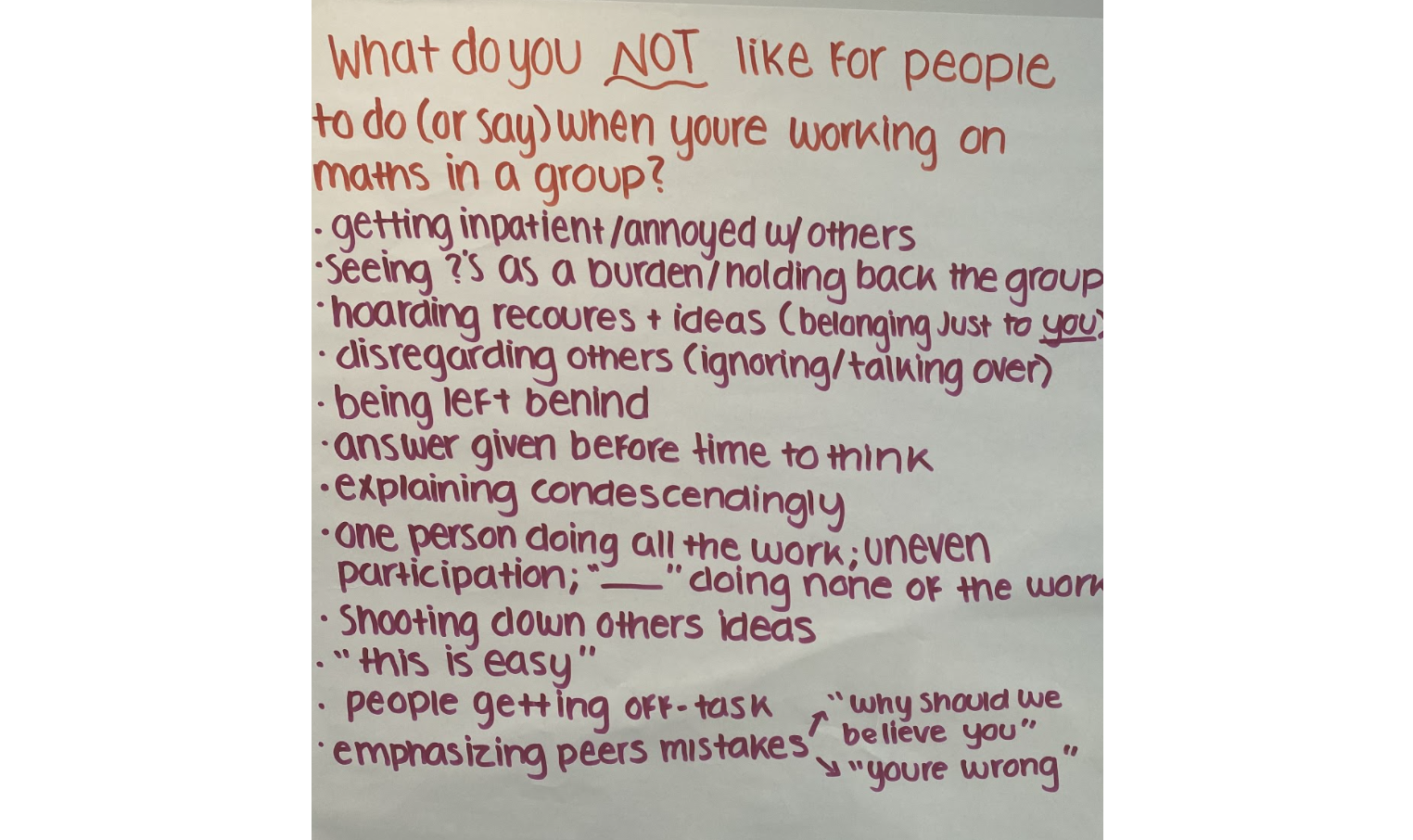

One thing I do in-person, always before we work on maths together in a group, is I ask the different groups in the room to sit and talk to each other about things they don’t like people to say or do when they’re working on maths together in a group. Students come up with these amazing, great things. And they say things like, “I don’t like it when somebody shows me what to do,” or “I don’t like it when somebody says, ‘This is easy,’ or ‘obviously’ or any of those kinds of words.” All the groups come up with some ideas.

I ask the different groups in the room to sit and talk to each other about things they don’t like people to say or do when they’re working on maths

Then I go to each group and say, “give me one of your things.” And we make a poster for the whole class together: “These are all the things we don’t like people to do.” And then we go and do it again, except for things we do like people to say or do. So this is beneficial in an online environment because the things in an online environment that people don’t like might be different for an in-person environment.

Classroom culture can be tricky. How do you build norms? Do you find it varies for online versus offline classes?

I think whenever I start classes, there’s always a lot of maths anxiety. It’s partly from being in a class with others, but also just your own internal fears. And so we often do readings around that and talk about it together. One of the things I most like to do in a maths class is have everybody write up before the first class what I call a ‘maths history’, where we ask them about their relationship with maths and where it came from. List any really good moments you’ve had, or any very bad moments you’ve had — usually people have bad moments in their history. And those are very helpful for me. I asked for them ahead of time. I read them. I take them into account when I’m teaching. And I do that online as well.

But it’s important to also give people space to talk about those issues. I have a really nice reading that I give people about how to interact in class. I give out that reading and we talk about it.

I’m giving people more time to think and talk online than offline, just to try and break down some of the barriers that not being together creates.

How do you wrap up your courses?

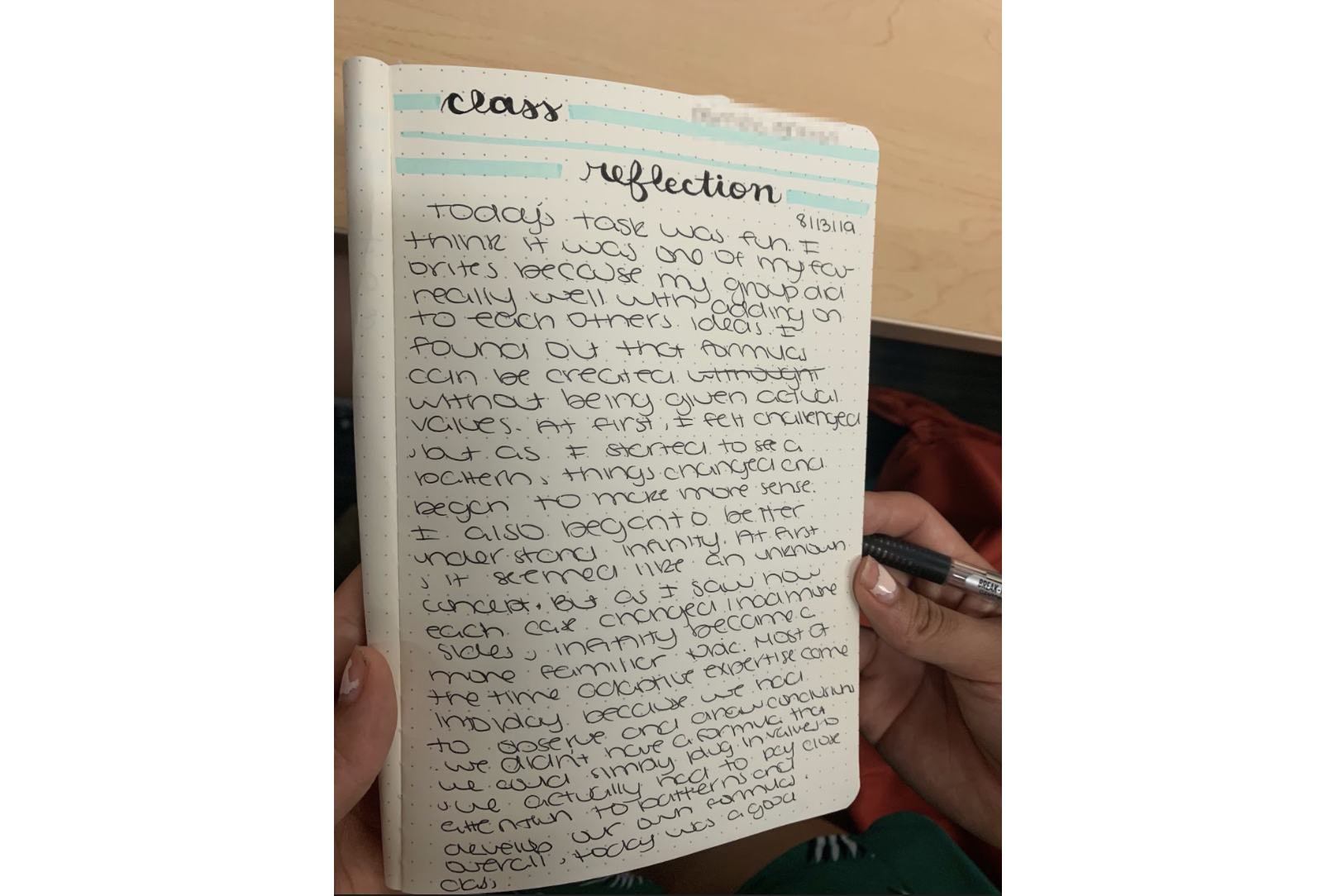

I often like people to reflect on their learning journey, whether this is a Stanford in-person class or an online class. With younger students, we asked for a reflection in the form of what we call a ‘letter to self.’ We say to the students: “write down a letter to yourself and think about some of the ideas you’ve got from this course, and add any boosting messages you want to give yourself.” Then we mail it out to them a few months later.

With my undergrads and grad students, sometimes I ask them to reflect on just the same: “What have you learned and what are you thinking about? What questions do you have?” I think that kind of reflection is really important. Psychologists — I hang out with psychologists sometimes — call it “writing is believing.” Because if you get somebody to write down what they’re thinking, it integrates much more.

I do this in my online lessons, too. I have an online class with students. At the end of every lesson, they are asked: “Write down for somebody who wasn’t here what the main messages from the lesson were.” That is very deliberately done so that they record the ideas.